Ace Hotel : Redefining The Hotel in the U.S.A. & its Cities

With clairvoyant location-scouting, Ace Hotels and other industry players are redrawing the map of cities we thought we knew.

On a stormy day in January, Kelly Sawdon, chief brand officer for the Ace Hotel Group, and Brad Wilson, the company’s president, stood inside an old furniture store in New Orleans, watching a construction worker push a sander across the floor. In two months, if all went according to plan, the space would be filled with guests and curious locals. But for now, coils of wire lay on the floor, and the thick smell of paint hung in the air.

Wilson, in a white construction hat, strode across the lobby, shouting over the din. “Unlike other properties we’ve worked on, this one wasn’t already a hotel, so there was a lot to be done upstairs,” he said. “But with the lobby, we’re hoping to preserve some of the original feel. The beautiful old moldings up there will stay.” He pointed. Here would be a Stumptown café, the first south of the Mason-Dixon Line; there, a stage for visiting musicians.

The Ace Hotel New Orleans opened its doors this spring, the eighth entry from the Ace Hotel Group—which, if you haven’t noticed, has been on quite the tear lately. But of course you’ve noticed: These days, no one can ignore Ace, even those who don’t wish to sleep in its loftlike rooms or sip artisanally roasted espresso in its artfully weathered lobbies. The brand continues to expand at a rapid clip. In the near future, if you visit a major American city—or just live in one—you might not stay in an Ace Hotel, but you may wind up in a neighborhood that Ace put on the map.

Co-founded in 1999 by Seattle club owner and entrepreneur Alex Calderwood, Ace has made a play of cheeky iconoclasm and a curatorial style that can border on precious (see the Portlandia sketch about the “Deuce Hotel” and its aggressively hip check-in staff). The look is familiar by now: bespoke art on the walls, guitars in the bedrooms, upbeat messages (“Everything Is Going to Be Alright”) emblazoned in the lobby. Love or loathe it, Ace’s house style has become so pervasive across the industry that new hotels are often described as “Ace-like”—be they indie brands such as Freehand, The Hoxton, and Mama Shelter, or the millennial-ready offshoots of big-name chains, with their sassy “Go Away” doorknob signs and pour-over coffee bars. “That emphasis on ‘local, authentic’ travel has gone mainstream,” says Greg Oates, senior editor at travel industry site Skift. For instance: “The concierges at Marriott’s Renaissance brand are called ‘Navigators’ and provide local travel tips, and InterContinental focuses on ‘insider’ or ‘in the know travel.’?”

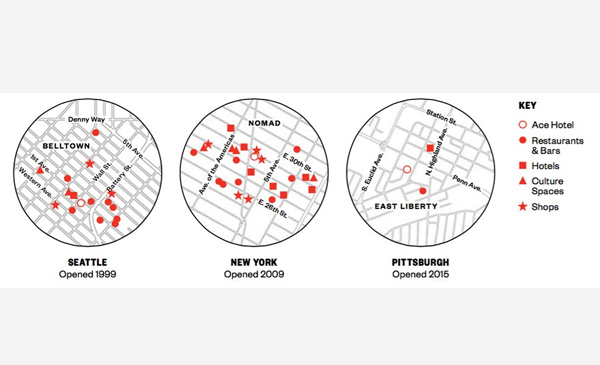

Yet as imitators abound, Ace has distinguished itself in another way: by taking an unorthodox approach to development, eschewing already-saturated locations for emerging ones. Opening a hotel is a multi-million-dollar gamble for any brand and its financial partners, so standard operating procedure is to choose locations based on the success of existing properties. But when the first Ace took root in an unremarkable patch of western Seattle, it was notable for having a club frequented by R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, and not much else. Belltown has been on the style map ever since. That first hotel, set in a former halfway house, felt more like a glorified hostel where a visiting band might crash after graduating from friends’ couches. Their friends probably lived in Belltown too.

A similar metamorphosis occurred a decade later in the dead center of Manhattan (emphasis on dead). What we now call the NoMad district, south of Times Square, was until 2009 an in-between zone of wig wholesalers and sidewalk patchouli-hawkers—before Ace took over an abandoned hotel and, with its deep leather couches and communal workspaces, created the hottest lobby scene in town. (The upmarket NoMad Hotel, a block south, followed three years later.)

In 2013, Ace opened its first European outpost, in East London’s gritty Shoreditch—an area overserved by vintage shops and bars but underserved by design-conscious hotels. Last December, an Ace arrived inPittsburgh’s up-and-coming East Liberty district. The brand has repeated the trick often enough that industry watchers refer to the “Ace Effect,” or the explosion of a neighborhood after a cool hotel moves in. Identifying those areas is something Ace’s development team has been uncannily adept at: They’re the place whisperers, the neighborhood foragers, the location scouts for a film that you and your art-student nephew will both want a cameo in.

“People ask if there’s a technique to choosing neighborhoods, and actually there is,” Ace’s Wilson says, “because it’s all in the relationships.” His colleague Sawdon notes that co-founder Calderwood’s greatest gift lay in making connections; he collected friends in creative circles, from visual artists to musicians to clothing designers, and delighted in mixing one group with another. He approached hotel development the same way—seeking introductions, asking questions, leaning hard on friends’ advice. And it’s how the brand has carried on in his absence. (Calderwood died of an apparent drug overdose in 2013.) Banding with so many creatives and entrepreneurs when opening its hotels, Ace is never short of networks to tap. That popularity translates to power, as Ace works with real-estate developers to attract like-minded retail brands, not only to the hotel but also to the surrounding streets. “We like to keep the people who inspire us close by,” Ace’s Sawdon says. “We’ve been lucky enough to anchor all of these disparate retailers, record stores, and pop-ups, and that ultimately allows us to engage and collaborate with more interesting and daring people.”

Wilson offers as an example the Ace Hotel Pittsburgh , which began in 2010 as a conversation between Matthew Ciccone, a local entrepreneur, and Eric Shiner, then curator of Pittsburgh’s Andy Warhol Museum. Ciccone had been active in an effort to revive East Liberty, a faded neighborhood not far from the Carnegie Mellon campus. “The great part about it was all these beautiful pieces of architecture that remained—churches, storefronts, an old YMCA,” Ciccone recalls. He was hoping to get a hotel into the area. Shiner suggested he speak to his friend Calderwood, who was curious but hesitant: London was in the works, as was a hotel in downtown L.A. But Ciccone kept in touch, and in 2014, his firm teamed with the Ace principals to develop a hotel—which wound up occupying that former YMCA. (The Ace Pittsburgh won a spot on Condé Nast Traveler’s Hot List last month.)

Investing in a fringe locale is a cultural choice as much as an economical one—a show of faith in a neighborhood’s potential, balanced with a hunch that it won’t transform itself too much. East Liberty,Pittsburgh, is well removed from downtown and from anywhere your mother might want to be, yet its mix of old-man bars and edgy art spaces jibes well with the Ace ethos. And that stately Presbyterian church across the street? Now the congregants, many of them dressed to the nines, flock to the Ace hotel’s restaurant for Sunday brunch. “Our feeling—and this was something Alex was particularly good at—is that you don’t want to just drop into a place and throw open the doors,” Sawdon says. “You want to become part of the community.” That notion has made the hotels gathering points in neighborhoods that didn’t have them. Walk into any Ace outpost and you’ll typically see locals meeting for drinks alongside overnight guests.

Their success has encouraged other hospitality brands to take a similar tack, putting hotels in places that might scare off mainstream developers. What Ace has done for low-profile neighborhoods, the Louisville, Kentucky–based 21c group has done for lower-profile cities, opening art-driven “museum hotels” in places like Louisville and Cincinnati. Four more hotels are now in the works, including one that just opened in a derelict Model T factory in Oklahoma City.

Craig Greenberg, president of 21c, won’t discount the possibility of going into established sections of major cities. “But it’s a unique and extremely exciting and satisfying experience to open a hotel in a place like an old factory,” he says. Working on the fringes has its challenges, Greenberg stresses. “If you’re going to an established area, it’s easier to get the required funding.” With an emerging location, investors can be cagey: Is there enough cultural infrastructure to support a hotel?

One solution, which 21c employed in Cincinnati, is the private/public partnership—the city teams with the brand and its investors to co-fund a hotel in order to reinvigorate an area. Greenberg points to increased foot traffic in neighborhoods where 21c has opened hotels, and to rising commercial rents, as indicators of the model’s success.

But as the market grows crowded with uniquely decorated hotels in transitioning neighborhoods, how long can the hipster-hotel bubble last? “Instead of being the eleventh Hilton-type brand downtown, you look to the fringe,” says Lauro Ferroni, senior vice president at real estate adviser JLL’s Hotels & Hospitality Group. “But one limitation is there are only so many interesting sub-markets.”

For now, Ace is showing it can keep adapting. In New Orleans, the Warehouse District had been farther along than East Liberty or NoMad—already home to the National World War II Museum and five of Donald Link’sacclaimed restaurants. A New Orleans–based architecture firm was brought in, while Roman and Williams, who’d worked on the Ace Hotel New York, collaborated on the interior design. Still, its industrial patina bestows a frontier cachet. Head up to the Ace’s rooftop pool and you can gaze over the aging brick buildings that give the area its name. Beyond are the towers of the Central Business District, and beyond that—unseen and unheard from the Ace—the neon throb of the French Quarter.

“To us, this location was the best of all worlds,” Sawdon says. “It’ll take you 15 minutes to walk to the Quarter. But you’re in a part of New Orleans you might not have explored, in a neighborhood we really love, and that’s loved by the people we love.” Sure, it’s a bit off the beaten path. But that’s the point, isn’t it?

Plus, if the Ace hotels weren’t on your radar already, right now they are offering great deals for summer stays at their locations around the world.

Written by Matthew Shaer