A tale of luggage gone wrong and it’s not because airlines lose a lot of bags

The poet Maya Angelou once said you can tell a lot about a person from the way they respond to three things: a rainy day, tangled Christmas lights, and lost luggage.

Maya, Maya. Where were you at 2 a.m. the dark night I arrived in Paris without my bags? I needed my suit for the next morning, not folksy aphorisms or your musings on why the caged bird sings. Personally, I find the caged bird sings most beautifully when he has his laptop charger and toothbrush.

We’ll never know quite how Dr. Angelou would cope with the news that a vacation’s worth of clean underwear has been flown to the wrong Portland. But she’s right to suggest that lost luggage is a near-universal experience. Every frequent traveler will at some point face the drifting tumbleweed on the baggage belt.

Still, if most of us have a tale of luggage gone wrong, it’s not because airlines lose a lot of bags.

Bar codes reduce delays by computerizing the task of ensuring that every bag that’s loaded on a plane is matched to a passenger who’s actually boarded

Photograph courtesy SITA.

It’s because we fly so much. In July alone, 53 million passengers boarded domestic flights. Only about one-third of 1 percent reported a mishandled bag. Given the phenomenal scale of American aviation (measured in seats and miles, the U.S. market is three times larger than any other) and our reliance on luggage-juggling hub airports, that’s an excellent result. Even caged birds are treated pretty well by modern air travel (though remarkably, they do get airsick): In July, U.S. airlines lost just one pet.

This success is largely due to the humdrum baggage tag. That random sticky strip you rip off your suitcase when you get home? It’s actually a masterpiece of design and engineering. Absent its many innovations, you’d still be able to jet from Anchorage to Abu Dhabi. But your suitcase would be much less likely to meet you there. (Disclosure: I am a pilot for an airline that’s not mentioned in this article.)

First a little history. In the old days—we’re talking steamships—there were two kinds of tags for luggage. Best known are the labels affixed to trunks. Often these were pure advertising for the shipping line, with no room for personal information—for some beautiful examples click hereand here. The other kind of tag—a destination tag—was more practical, though still aesthetically pleasing. One side often bore the line’s logo, as in this classic Cunard White Startag. The reverse held information such as the passenger’s name, destination, stateroom and whether the bag was “Wanted in Stateroom” or “Not Wanted on Voyage.”

Early on, airlines offered labels that mimicked maritime-style advertising stickers, with lovely results. But initially, airlines had no need for destination tags: As the International Air Transport Association explained to me, “a passenger’s chauffeur would drive the passenger to the aircraft side, and stewards would load the passenger’s bags directly from the car to the aircraft.” Nice.

As air travel expanded beyond the perfumed realms of the chauffeured, destination tags became a necessity. Maritime tags were the model, but with the occasional important tweak, as Melissa Keiser, an archivist for the National Air and Space Museum, points out. What is inconsequential to ocean liners and railways, but vital to airlines? Weight. It’s critical that airlines know how much bags weigh, and how they’re distributed around the plane. According to Keiser, a space for weight was commonplace on airline tags by the 1920s. “Separable” baggage tags, which featured a removable receipt for travelers, had first been developed for railways in 1882 (check out the excellent patent application). By the 1930s, says Keiser, they too had been widely adopted in aviation.

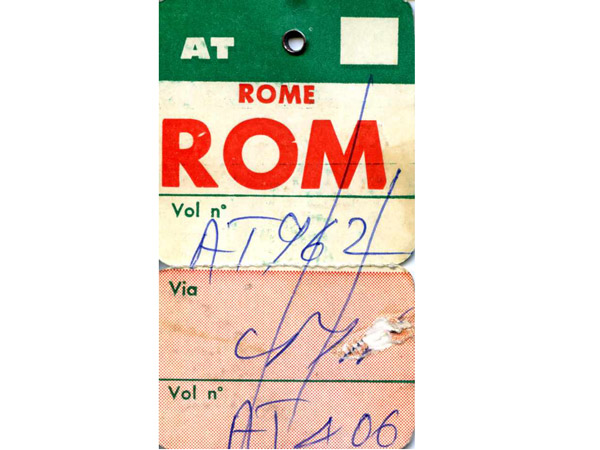

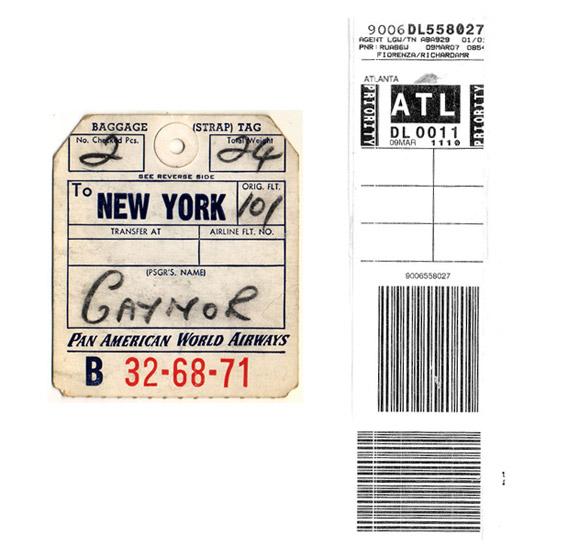

But as aviation grew still further, airline tags shed their maritime and railway heritage. Compare the two tags below: a Pan Am tag from the 1950s, and a modern tag of the sort an airline will put on your bag today.

The modern tag is known as an automated baggage tag, and was first tried by many airlines in the early 1990s. Perhaps the earliest airline to implement ABTs system-wide was United, in 1992, according to Jon Barrere, a spokesperson for Print-O-Tape, a tag manufacturer and United’s partner on the project. Let’s examine in detail the myriad improvements offered by the ABT, which symbolize as perfectly as anything air travel’s transition from a rare luxury for the ultra-rich to safe, effective transport for a shrinking planet.

Let’s look first at how an ABT is made. In the interconnected, automated, all-weather world of modern aviation, tags must be resistant to cold, heat, sunlight, ice, oil, and especially moisture. Tags also can’t tear—and crucially, if they’re nicked, they must not tear further—as the bag lurches through mechanized airport baggage systems. And the tag must be flexible, inexpensive, and disposable. Plain old paper can’t begin to meet all these requirements. The winning combination is what IATA’s spokesperson described as a “complex composite” of silicon and plastic; the only paper in it is in the adhesive backing.

Bar codes reduce delays by computerizing the task of ensuring that every bag that’s loaded on a plane is matched to a passenger who’s actually boardedPhotograph courtesy SITA.

Bag tags must meet another set of contradictory requirements. They must be easy to attach, but impossible to detach—until, that is, the bag arrives safely at its destination and the traveler wants to detach it. Old tags were fastened with a string through a hole, but mechanized baggage systems eat these for breakfast. The current loop tag, a standardized strip of pressure-sensitive adhesive, looped through a handle and pressed to form an adhesive-to-adhesive bond, debuted with the ABT in the early ’90s. And the ABT, unlike string tags and earlier loop-y tag ideas, is easily attached to items that lack handles—boxes, say. Simply remove the entire adhesive backing and the loop tag becomes a very sticky sticker.

The simple genius of the looped tag alone explains why so few bags get lost. On a string-tied tag, according to a spokesperson for Intermec, a tag and printer manufacturer, “the primary stress is applied to a very small section of the tag. With looped tags, force is distributed over the entire width of the tag.” Of the few bags that are lost these days, only 3 percent involve “tag-offs,” the industry term for a detached tag. It almost never happens. Thank you,oh looped tag.

Of course while tags must remain rigorously attached, they must also be easy for passengers to remove. Intermec’s spokesperson raves about the adhesive’s “excellent flow properties”—in layman’s terms, simply grab the loop from the inside, with two hands, and gently pull apart to remove the tag. A couple of other clever innovations: Like the tags themselves, the adhesive must be all-weather. Early adhesives couldn’t cope with extreme cold, so snowy tarmacs would end up littered with detached tags (and lost bags). Also, passengers don’t want sticky residue left on their bag’s handles—so the adhesive’s backing is designed to stay in place on the inside of the loop.

Finally, let’s look at what’s on the tag itself. In the old days, tags were blank and would be filled in by hand, according to a spokesperson for SITA, an aviation technology group. Later on tags preprinted with the destination were introduced, eventually bearing the three-letter airport codes we know and love today (and some we no longer know—such as IDL, for Idlewild, the previous name for New York’s JFK Airport). As airline operations became more complex,elaborate color schemes were designed to help handlers quickly identify where a bag was bound.

But preprinted tags, manually read by baggage handlers, couldn’t cope with the world’s ever-growing volume of passengers and bags, let alone the increase in connecting flights with ever-shorter connecting times at ever-bigger and busier airports. The solution was the ABT’s combination of two features: custom printing and a bar code.

Just as you can track, step-by-step, a package you’ve sent by FedEx, airlines use bar-coded tags to sort and track bags automatically, through the airport, and across the world. That’s a huge change from the old days, when bags were dropped into the “black box” of a manually sorted baggage system. But crucially, an ABT doesn’t just contain a bar code—it’s also custom-printed with your name, flight details, and destination. That made the global implementation of ABTs much easier, because early-adopters could introduce them long before every airport was ready—a huge advantage when it comes to seamlessly connecting the world’s least and most advanced airports. And of course, ABTs can still be read manually when systems break down.

While bar codes have changed many industries, aviation has made special use of them. For example, bar codes reduce delays by computerizing the task of ensuring that every bag that’s loaded on a plane is matched to a passenger who’s actually boarded—an important security measure. And rough-and-tumble baggage systems present a much more challenging and three-dimensional environment than, say, a supermarket checkout. So note how the ABT’s bar code makes two appearances on the tag, offset by 90 degrees. It’s a small tweak that greatly improves readability by automatic and hand-held scanners.

Note, too, the small extra labels that each bear a copy of the bar code. Technically known asbingo tags, removable stubs, or stubbies, these were originally detached to help airlines track which bags were loaded. These days they’re often placed on your bag as another safeguard against a detached tag. (Ironically, stubbies from your previous flight can confuse airport scanners on your next flight—be sure to remove them after each trip.)

What’s next for bag tags? RFID tagging, which allows bags to be identified wirelessly: Think electronic toll collection on highways. Hong Kong, an early adopter, deployed RFID tags airport-wide in 2008. Until most airports can handle RFID tags, however, RFID tags can’t replace today’s standard bag tags. An early work-around was to add an extra RFID sticker to bags; now, the RFID tag can be embedded in the standard ABT loop tag. Other bag tag developments include self-tagging at the airport, as well as home-printed bag tags. But home-tagging passengers have to fold the tag into a plastic display case—hardly a high-tech solution.

In the very long term, perhaps the answer is the permanent bag tag—a durable, RFID-equipped tag that’s yours to keep and attach to whatever bag you’d like to check in. Launched in Australia in 2010 for certain domestic flights, permanent tags make checking in a bag nearly painless. But these permanent tags can’t go global until everyone’s ready to use them. And there’s no manual backup.

Permanent tags may offer one unexpected and welcome advantage. Melissa Keiser, the Smithsonian’s archivist, laments that by the 1950s, practical concerns eliminated the last vestiges of beauty from luggage tags. But with permanent tags, the RFID mechanism is hidden inside, and there’s no need for any data or machine-readable codes to appear on the tag itself. If permanent tags ever do go global, then in one sense they’ll be a return to the golden age of travel: There’ll be no excuse for them to not look good.

.

By Mark Vanhoenacker|Posted Thursday, Oct. 4, 2012, at 2:30 AM ET